‘The Sonic Ecology of the Adivasi Landscape’ (2024)

This short film takes you on a journey through soundscapes shaping Adivasi landscapes of Jharkhand. The Adivasi (Indigenous) communities of India are among the most marginalized communities and since colonial times until this day, under constant threat of land right violations. Mineral extraction is creating space for industrial, dominating sounds. Environmental sounds such as natural sounds and cultural sounds such as oral traditions and crafting sounds, are becoming endangered. This relationship between space, sound and ourselves as mediators, takes center stage. Just as we are affected by the sounds in our surroundings, we can also mediate our sonic environment and its impact on the ecosystem. Even in the face of mineral extraction, birds will sing, water will flow, Adivasis keep on spinning their thread and let their voice hear more than ever. The Adivasi soundscapes tell a story of loss, but also of hope. They call for action against ecological and cultural destruction. This short film is only a first step. It shows that if we truly listen, we can find resonances that lead to new connections — and perhaps even to justice.

Filmmaker Shankhu Toppo (member of the Oraon community) and film student Luca Verhaeghe researched the displacement issue of the Adivasi people of Jharkhand through a sensory approach. By handing out the camera and sound recorder, they used a participative filmmaking approach when engaging with the Oraon community. Weaving together stories of land justice and human dignity. Below, you will find more information about how this film was part of Luca’s master’s dissertation in Film and Visual Culture at the University of Antwerp.

Contact Resonant Earth for access to the full film.

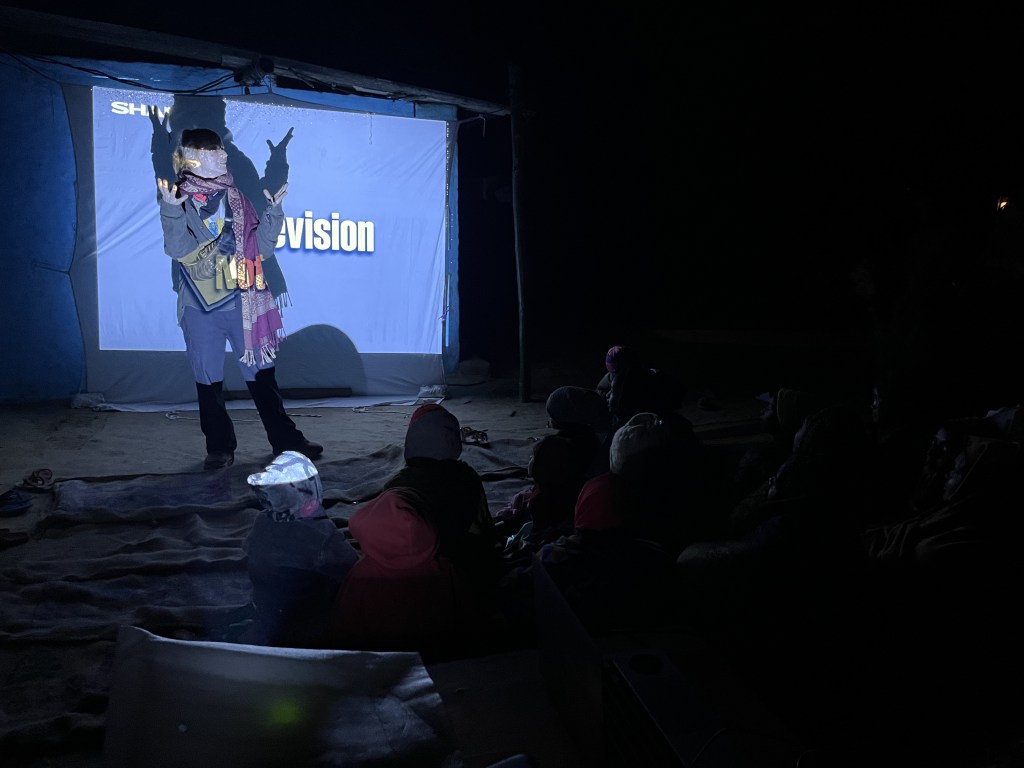

Community Screening in Sidrol

On December 11th 2024, we organized the screening of our short documentary ´The Sonic Ecology of Adivasi Landscapes’ in Kotari, one of Jharkhand’s Adivasi villages in the Burmu disctrict. This is the same village where the film was created in close collaboration with the local community.

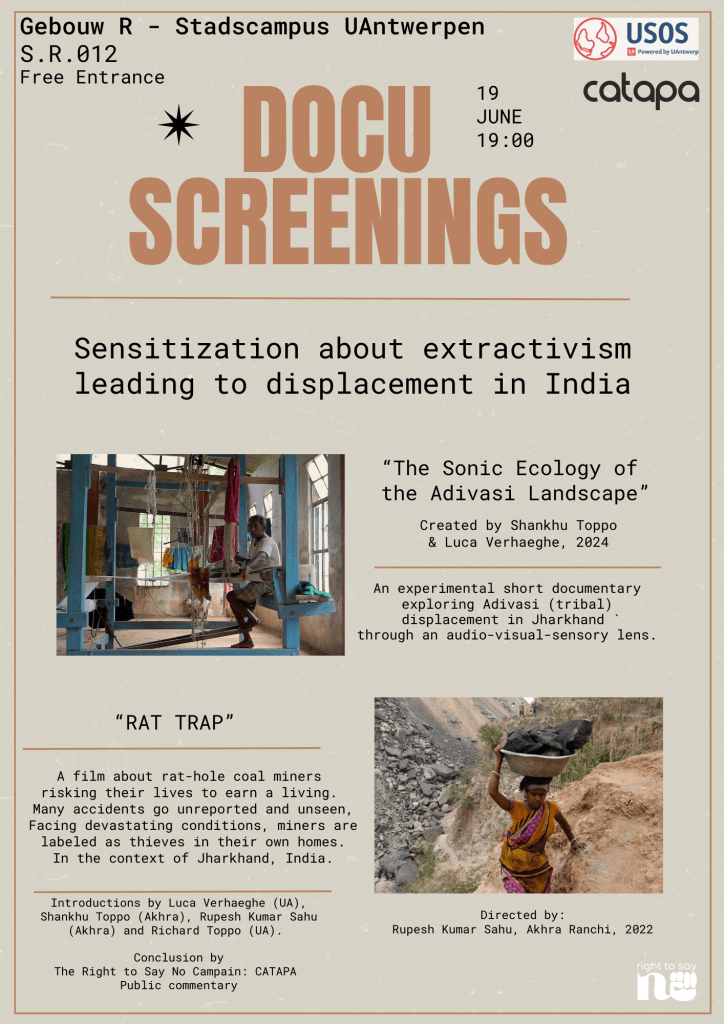

Documentary screenings about

The Consequences of Mining in Jharkhand, India

On 19th of June 2024, Luca presented the short film “The Sonic Ecology of the Adivasi Landscape” made by Resonant Earth during a student exchange program to Jharkhand (India), organised by USOS vzw and the Universiteit Antwerpen.

Together with the attendees, we reflected on the different ways our senses were engaged with the movie and wondered what the Adivasi soundscapes tell us about our relationship with the land. Then we had the honour to listen to postdoc student Richard Toppo telling us more about the historical context of Adivasi people, facing injustice until today.

To picture this context more concretely, the movie “Rat Trap”, made by Akhra Ranchi, was screened with an online introduction from director Rupesh Sahu. This movie zooms in on the harsh reality of illegal coalminers in Jharkhand. We closed the evening with a message of hope through the presentation of “the Right to Say No” campaign. It is a campaign by CATAPA fighting mineral extraction and unjust land acquisition in South-America.

It was an unforgettable evening which could never been facilitated without the help of CATAPA and USOS vzw!

We were very grateful for everyone who joined listening to the Adivasi stories, sharing thoughts and feelings, to continue weaving stories towards global land justice and human dignity.

Collaborative Filmmaking and the Sonic Ecology of Adivasi Landscapes

How can multisensory and decolonial approaches contribute to a better understanding of Adivasi land dispossession and enhance transcultural resonance?

Master’s Thesis (Luca Verhaeghe, 2024)

In Jharkhand, Eastern India, where the Adivasi communities see their rhythms and lives as inseparably connected to the ancestral land, the expansion of coal mines leads not only to environmental destruction but also to the erosion of their culture. This research highlights a decolonial and multisensory approach that, through a collaborative film, visualizes the context of Adivasi land dispossession and the accompanying soundscapes.

How Does Displacement Sound?

The Adivassi, the Indigenous people of Jharkhand, have a rich culture filled with songs, dances, and stories, shared in their central gathering space, the Akhra. However, the pressure of development projects led by the demand for minerals has often violently forced communities to leave their land. Displacement uproots not only their homes but also their songs, dances, and memories.

As a visual etnography student, I aimed to move beyond mere observation. What if the story of the Adivasi could not only be read or seen but also felt and heard? With this question in mind, a collaborative experimental short film, The Sonic Ecology of Adivasi Landscapes, was developed, where sound serves as a bridge to evoke resonance.

How Multisensory Research Fosters Connection

This research applied a unique approach: a multisensory, feminist, and participatory methodology. Traditional scientific methods, often patriarchal and colonial in nature, tend to reduce complex human experiences to mere data, consisting of jargon accessible only to a small, academic audience.

Through interviews, perception analyses, and field recordings, I explored how soundscapes reflect the Adivasi experience. Sounds such as hands cultivating the land, weaving looms, rustling forests, and the rumble of mining machines formed the foundation of our film. The film not only highlights the threats these communities face but also their resilience.

Collaboration with the local documentary group Akhra and in particular with Shankhu Toppo, was vital. Together, we developed a participatory process that gave space to both the voices of the Adivasi and the vision of us as filmmakers. The result is not a traditional documentary but rather an experimental composition of sounds, images, and silences that challenges the viewer to listen more deeply.

This work demonstrates how a decolonial, multisensory approach can bridge the gap between communities and researchers. Sound, often undervalued in research, can play a powerful role in conveying complex realities. By collaborating with local communities and challenging traditional research norms, we can enforce transcultural resonance with voices that are often unheard.